Solitude and Hope: Y'all Come Visit!

Publick and Privat Curiosities: Articles Related to News, Politics, Society, Gay Issues, Psychology, Humor, Music and Videos.December 30, 2005

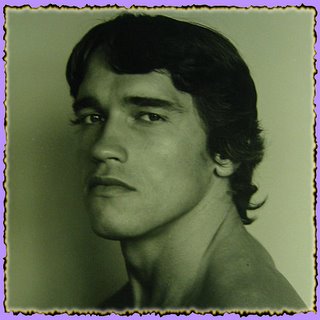

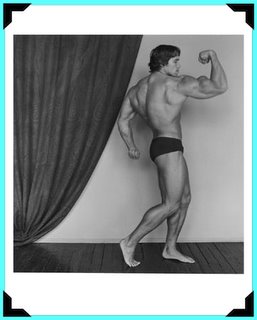

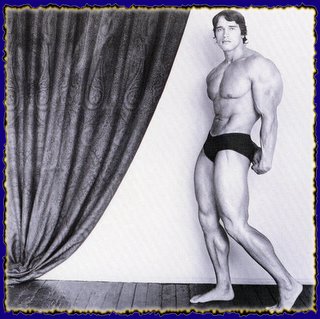

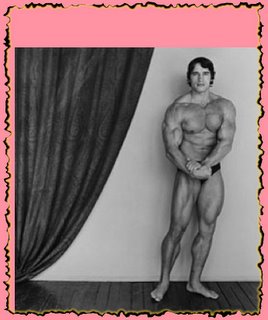

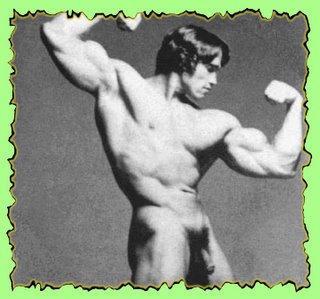

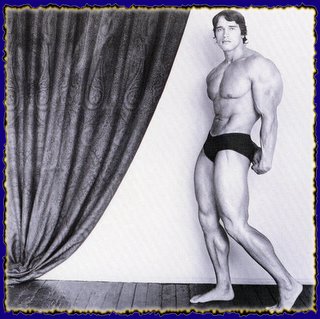

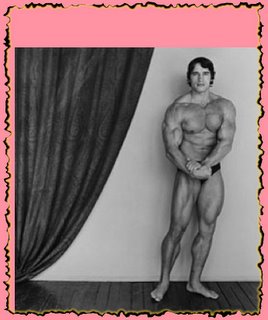

Arnold Schwarzenegger: Baring All...Almost...

Gary Stochl, the newly discovered Chicago street photographer discussed in the last posting, worked in isolation for more than forty years. His long journey teaches us the importance of devotion, perseverance, and personal vision. His story suggests that many of us should care a bit less about our careers and reputations and a bit more about our work. Stochl's unwavering commitment recommends humility when some of us confidently assume that we know everything about our own fields of work.

Schwarzenegger, in contrast, was a personality driven to achieve international notoriety. Immediately after arriving in the United States, he curried the favors of anyone who could promote his ambitions, not infrequently extremely wealthy older men who were infatuated with his sturdy, muscular physique. Another champion of his hunger for fame was Robert Mapplethorpe, the openly gay, lascivious photographer who was infamous, in part, for his body of porn/art photography. Mapplethorpe, enamored of Schwarzenegger, was quick to become one of the growing group of people who lionized and fawned over Arnold. And Scharzenegger was quick to nourish those feelings in order to further his own career. He posed for the first six of the pictures below, as well as for many others. The last ("peekaboo") photograph of Arnold coyly disrobed is probably the work of another photographer.

The motivation for this posting is not a purient one. Rather, it is an illustration of one man's calculated, seductive enshrinement of the worship of Flesh and Muscle. A later discussion will examine this deeper issue, specifically the replacement of "the world of the words" by the "world of Flesh and Muscle."

Schwarzenegger, in contrast, was a personality driven to achieve international notoriety. Immediately after arriving in the United States, he curried the favors of anyone who could promote his ambitions, not infrequently extremely wealthy older men who were infatuated with his sturdy, muscular physique. Another champion of his hunger for fame was Robert Mapplethorpe, the openly gay, lascivious photographer who was infamous, in part, for his body of porn/art photography. Mapplethorpe, enamored of Schwarzenegger, was quick to become one of the growing group of people who lionized and fawned over Arnold. And Scharzenegger was quick to nourish those feelings in order to further his own career. He posed for the first six of the pictures below, as well as for many others. The last ("peekaboo") photograph of Arnold coyly disrobed is probably the work of another photographer.

The motivation for this posting is not a purient one. Rather, it is an illustration of one man's calculated, seductive enshrinement of the worship of Flesh and Muscle. A later discussion will examine this deeper issue, specifically the replacement of "the world of the words" by the "world of Flesh and Muscle."

December 27, 2005

George Stochl: Reborn in 2005

A HOLIDAY GIFT

"What a great story." That's what everyone says when they learn about Gary Stochl and his work (and I hope that you'll think the same). It is a great story, at once both uplifting and perplexing. Stochl's narrative is one of long-term commitment, ambition, talent, and an intensely personal vision. It's also a tale of isolation, which forces us to question our assumptions about how American artists, working today, are generally entangled in the complex web of the artistic community: schools, museums, galleries, funders, dealers, curators, critics, collectors, and publishers. What happens to an artist when he or she has no contact with that artistic community? Is it possible to be a serious artist without those connections-and what happens to the work of an isolated artist?

In late Spring 2004, Bob Thall returned to his office in the Photography Department at Columbia College (Chicago) to find a cluster of students waiting for the department's academic advisor. There was also an older fellow sitting there with a paper shopping bag. The secretary looked up with a troubled expression, nodded at him, and said, "Uh, Bob, this gentleman wants to show someone some photographs." Mr. Thall was busy, but he invited him into his office. Thinking that he was a returning student, perhaps an Art/Design major who wanted to place out of his photography requirement, Mr. Thall thought that this matter could be handled quickly. Gary Stochl sat down and said that he wasn't interested in taking any classes-that wasn't why he was there. "No?" Mr. Thall asked.

"No, I've been doing photography for forty years and really haven't shown my work to anyone. I thought it was time I started to do that. You're a Photography Department, so I thought I'd come here." He reached into the bag and pulled out a stack of loose prints perhaps eight inches high. Uh-oh, Mr. Thall thought, this is going to mess up my afternoon. "Listen," he said, "I have a meeting in just a few minutes, but I'll be happy to take a fast look at these before I have to go."

He started to flick quickly through the photographs. Stochl told Mr. Thall later that he was shocked at how little time he spent with those first ones. Well, Mr. Thall hadn't expected much. But, after about fifteen or twenty images, he had the odd feeling that this strange, chance meeting might be something exceptional, so he slowed down a bit. After another ten or twenty prints, he was no longer hurrying through Mr. Stochl's work. He'd forgotten about the fictitious meeting, and also about all of the very real things he had to do that afternoon.

Out of the 300 or so photographs he saw that first day, all of them were accomplished, serious images that consistently pursued a sophisticated visual and emotional agenda. Perhaps half the photographs were really excellent, and, of those, fifty or so were the kind of memorable, extraordinary images that notable photographers build their careers on. These pictures were reminiscent of iconic images that one expects to see in the history of photography books. One didn't expect to see them pop out of a shopping bag at a chance meeting.

He spent two hours with Stochl that first day. His colleagues Dawoud Bey and Greg Foster-Rice walked by, and he called them in to meet Stochl and see his work. Like Mr. Thall, they were stunned by the photographs. They tried to give him a crash course in getting his work out, covering topics such as editing and presentation. Finally, they asked him to do a preliminary selection and meet with them again. At the second meeting, they worked with him to edit a tight, representative sample. They felt that he needed to pare the large stack of photographs down to a number that a curator or dealer could manage on a first viewing. It was hard work. There were simply too many extraordinary images, and it was difficult to get down to a reasonably sized set of photographs.

It was clear that Gary Stochl's work was significant, and it was important that his photographs be known and have a public life in the photographic medium. As a part of the Chicago photographic community, it was appropriate that the Photography Department of Columbia College (Chicago) help. They matted some of the work and then made some calls to arrange introductions. Of the many people who took the time to see Stochl's work, the open-mindedness, enthusiasm, and generosity of David Travis, Liz Siegel, and Kate Bussard at the Art Institute of Chicago, photography dealer Shashi Caudill, collector Dick Press and Gregory Knight at the Chicago Cultural Center was impressive. It was also striking to watch how quickly Gary Stochl learned the ropes, jumpstarting a career that had been silent forty years.

There are two great traditions in modern American photography that are of

particular interest in this story. One might be called "Personal Documentary." This strain of photography began with Walker Evans. Photographers in this tradition may make highly descriptive and objective-looking images, but the real point is to collect evidence to support their views of life, no matter how subjective.

The tradition that counterweights, even opposes, this passionate advocacy of a subjective view of life is "Modernist Formalism." Photographers within this tradition pursue serious investigations into the nature of the photographic medium, thinking in terms such as "camera vision" and "picture space," indicating an interest in the reality of the photograph, independent of the "real" world. These photographs teach us about the photographic medium, and, perhaps more importantly, they attempt to make us conscious of our own thought processes and of the ways in which we see (or ignore) the visual world.

Many photographers working in Chicago have pursued either an intensely personal viewpoint or provocative, formalist work. Both traditions are worthwhile and challenging, but very few photographers anywhere ambitiously pursue both tracks at once. It's always difficult to reveal successfully an intensely personal and consistent view of life while integrating a sophisticated agenda of formal experiments and innovations. For the few who do try to combine these traditions, the photographic success rate is understandably low: lots of strikeouts, a hit every so often, and rarely a home run. What was so astonishing about seeing those first stacks of Stochl's photographs was that, although he was consciously trying to accomplish this difficult balancing act, the normal odds didn't seem to apply to him. He hit it out of the park over and over again.

Gary Stochl first saw the photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson (and, later, Robert Frank) in the 1960s and was inspired to buy a Leica camera to begin photographing. Frank's influence is clear in Stochl's work, but while Frank's photographs express a political and social reaction to an entire nation, Stochl's photographs of life on the streets of Chicago deal with the texture and drama of single lives. Stochl visually describes ordinary people as individuals, not as examples of American stereotypes. He photographs a diverse range of Chicagoans with an alert exactness that is neither flattering nor unkind.

Gary Stochl's photographs rarely contain the dramatic moments or the weird, ironic juxtapositions that often attract street photographers. Instead, with unnerving directness and consistency, Stochl's photographs present people who seem to struggle with the difficulty and loneliness of normal everyday life. The honesty and grimness of the images can at times be disturbing and, like all good art, leave the viewer with an altered sense of the world. From the first photographs he made in the 1960s to photographs he made last month, Stochl's images present a consistently tough-minded and dark view of life.

Simultaneously, his photographs also pursue a program of visual experimentation with remarkable skill, intelligence, and patience. Stochl often constructs complex photographs in which the frame is split into two or three sections, each with subtly different, but crucially interconnected content. In other photographs, reflections, openings in walls, barriers, and other elements not only separate the people photographed, but also relate them to the larger urban landscape. In some images, implausible coincidences of tone and gesture are used to reveal subtle and important content. Exquisite moments of light and shadow are often employed in the photographs to create a dramatic stage set for ordinary life in a major American city.

It is astonishing that Gary Stochl has photographed intensively for forty years, and continues to work at an admirable pace, without any of the normal support and encouragement artists typically seek and enjoy. He had no teachers, no exhibitions until his first show in the Fall of 2003, no community of like-minded photographers, no dealer, no sales, no commissions, no publications, no reviews, no grants, and no job in the field. Nothing. Absolutely nothing for almost forty years. And yet he's consistently worked with astounding dedication, self-discipline, and ambition, all bedrocks of the creative process.

Ending this story, it is valuable to reiterate the powerful observations made in the introduction: Stochl's story is a tale of isolation, which forces us to question our assumptions about how American artists, working today, are generally entangled in the complex web of the artistic community: schools, museums, galleries, funders, dealers, curators, critics, collectors, and publishers. What happens to an artist when he or she has no contact with that artistic community? Is it possible to be a serious artist without those connections—and what happens to the work of an isolated artist?

Like all great stories, this one holds some lessons. Gary Stochl's long journey should re-teach us the importance of devotion, perseverance, and personal vision. His story suggests that many of us should care a bit less about our careers and reputations and a bit more about our work. His story recommends humility when some of us confidently assume that we know well the recent history of photography, that we know who’s who and exactly what’s been done in photography. His photographs remind us that descriptive photographs can gather extra meaning and importance as time goes by. Although Stochl never intended to document downtown Chicago, his images will, over time, become a wonderful, important historical resource for the city. Finally, Gary Stochl's story can teach us that great work can eventually find the audience it deserves.

The University of Chicago Press published a book of Stochl's photographic work last year, and a second volume is currently scheduled for publication.

December 25, 2005

Hanukkah and Christmas: Happy Holidays to You!

George W. Bush: "When I Am The Dictator"

INTRODUCTION:

At first, I read Friday's (12/23/2005) New York Times' editorial about Dick Cheney's role as the driving force behind the establishment of an astonishing expansion of presidential powers with great anger. However, after some reflection I have realized that George W. Bush's joke about governing as a dictator was and is no joke.

The proliferation of ever more repressive power over the American people, as well as the increasing limitations upon our personal freedoms, will not successfully be confronted simply by rage or anger. We must attempt to achieve a deeper understanding of what lies beneath these forces of domination.

Some years ago, Mitscherlich (1993) associated the concept of a "Society Without a Father" with the emergence of fascism and Hitler's rise to power in Germany. What might this mean for the present situation in the United States? First, looking at George W. Bush, one begins to question the nature of his relationship with his own father. There are, indeed, strong suggestions that his father was experienced as absent and that there was, then, no real competition with his father to lose. In the absense of such competition, an authentic sense of conscience is not established. This results, on the one hand, in a personal life characterized by an impaired sense of self-control (note Bush's admitted debauchery during his years at Yale, as well as his acknowledged history of substance abuse). This can lead to at least two situations.

First, even with the reliance upon his wife an external source of support for his personal life (as a "conscience" alias), this may well still leave him feeling vulnerable to a strong fear of internal fragmentation and loss of control. Thus, the need to project his fears onto the outside world, and the attempt to over-control the external environment, including his presidential control over us. In other words, George Bush as a mass leader acts as if he is superior to conscience, demanding a regressive obedience from us, as if we were unknowing children. Lacking a tie to the father, for Bush a genuine father-son conflict was absent at the time that the conscience was to be formed and ties to it were to be established.

In addition, with the unavailablity of a political sense of conscience, Bush has been forced again to seek and rely upon sources of external guidance in this area. Lacking even a primitive sense of self-cohesion, he has turned to those who will provide him with the mirroring transference needs of unqualified praise and admiration. Consequently, Bush has come to rely upon men such as Cheney, Rove and DeLay. More broadly, he has come to embrace the words of the born-again, evangelical Christian movement. However, lacking his own sense of internal conscience and judgement, Bush is left unable to evaluate either the motivations or guidance of those upon whom he relies.

Thus, on the one hand we are left with a president blindly following the dictates for ever-more expanding power, oppression of the less fortunate and the legitimization of abuse, even torture of those who question or oppose the proliferation of American political domination throughout the world. On the other hand, Bush's reliance upon the evangelical Christian movement as a source of conscience has led to the unprecedented intrusion of one particular religious sect or cult into the course of governmental and public life. More perilous, it has resulted in major governmental decisions being made in accordance with and to satisfy the dogmas of that particular religious movement.

Secondly, what makes our situation ever more dangerous is the convergence of a president thus impaired with the current state of American society. We are now a society that increasingly feels alienated from public life, forced into taking the role of passive victims of the immensely wealthy, technological advances at a rate almost beyond our grasp and unbelievable, corrupt politicians more interested in their own needs than those of their constituents. As a society, then, we have rapidly become a "fatherless" society, feeling a lack of internal control and self-determination.

Thus, largely unaware of our motivation, many of us desperately have sought a solution by making, as with George W. Bush, a distraught attempt to rigidly control our external world—and one aspect of this attempt has been to seek an ally to serve as The Father, The Law, and The Authority. We are making a dangerous liaison with Bush, who is desperately seeking the same thing.

These are dangerous times: History repeats itself.

THE N.Y. TIMES EDITORIAL:

"MR. CHENEY'S IMPERIAL PRESIDENCY"

George W. Bush has quipped several times during his political career that it would be so much easier to govern in a dictatorship. Apparently he never told his vice president that this was a joke.

Virtually from the time he chose himself to be Mr. Bush's running mate in 2000, Dick Cheney has spearheaded an extraordinary expansion of the powers of the presidency - from writing energy policy behind closed doors with oil executives to abrogating longstanding treaties and using the 9/11 attacks as a pretext to invade Iraq, scrap the Geneva Conventions and spy on American citizens.

It was a chance Mr. Cheney seems to have been dreaming about for decades. Most Americans looked at wrenching events like the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal and the Iran-contra debacle and worried that the presidency had become too powerful, secretive and dismissive. Mr. Cheney looked at the same events and fretted that the presidency was not powerful enough, and too vulnerable to inspection and calls for accountability.

The president "needs to have his constitutional powers unimpaired, if you will, in terms of the conduct of national security policy," Mr. Cheney said this week as he tried to stifle the outcry over a domestic spying program that Mr. Bush authorized after the 9/11 attacks.

Before 9/11, Mr. Cheney was trying to undermine the institutional and legal structure of multilateral foreign policy: he championed the abrogation of the Antiballistic Missile Treaty with Moscow in order to build an antimissile shield that doesn't work but makes military contractors rich. Early in his tenure, Mr. Cheney, who quit as chief executive of Halliburton to run with Mr. Bush in 2000, gathered his energy industry cronies at secret meetings in Washington to rewrite energy policy to their specifications. Mr. Cheney offered the usual excuses about the need to get candid advice on important matters, and the courts, sadly, bought it. But the task force was not an exercise in diverse views. Mr. Cheney gathered people who agreed with him, and allowed them to write national policy for an industry in which he had recently amassed a fortune.

The effort to expand presidential power accelerated after 9/11, taking advantage of a national consensus that the president should have additional powers to use judiciously against terrorists.

Mr. Cheney started agitating for an attack on Iraq immediately, pushing the intelligence community to come up with evidence about a link between Iraq and Al Qaeda that never existed. His team was central to writing the legal briefs justifying the abuse and torture of prisoners, the idea that the president can designate people to be "unlawful enemy combatants" and detain them indefinitely, and a secret program allowing the National Security Agency to eavesdrop on American citizens without warrants. And when Senator John McCain introduced a measure to reinstate the rule of law at American military prisons, Mr. Cheney not only led the effort to stop the amendment, but also tried to revise it to actually legalize torture at C.I.A. prisons.

There are finally signs that the democratic system is trying to rein in the imperial presidency. Republicans in the Senate and House forced Mr. Bush to back the McCain amendment, and Mr. Cheney's plan to legalize torture by intelligence agents was rebuffed. Congress also agreed to extend the Patriot Act for five weeks rather than doing the administration's bidding and rushing to make it permanent.

On Wednesday, a federal appeals court refused to allow the administration to transfer Jose Padilla, an American citizen who has been held by the military for more than three years on suspicion of plotting terrorist attacks, from military to civilian custody. After winning the same court's approval in September to hold Mr. Padilla as an unlawful combatant, the administration abruptly reversed course in November and charged him with civil crimes unrelated to his arrest. That decision was an obvious attempt to avoid having the Supreme Court review the legality of the detention powers that Mr. Bush gave himself, and the appeals judges refused to go along.

Mr. Bush and Mr. Cheney have insisted that the secret eavesdropping program is legal, but The Washington Post reported yesterday that the court created to supervise this sort of activity is not so sure. It said that the presiding judge was arranging a classified briefing for her fellow judges and that several judges on the court wanted to know why the administration believed eavesdropping on American citizens without warrants was legal when the law specifically required such warrants.

Mr. Bush and Mr. Cheney are tenacious. They still control both houses of Congress and are determined to pack the judiciary with like-minded ideologues. Still, the recent developments are encouraging, especially since the court ruling on Mr. Padilla was written by a staunch conservative considered by President Bush for the Supreme Court.

The New York Times

December 23, 2005

At first, I read Friday's (12/23/2005) New York Times' editorial about Dick Cheney's role as the driving force behind the establishment of an astonishing expansion of presidential powers with great anger. However, after some reflection I have realized that George W. Bush's joke about governing as a dictator was and is no joke.

The proliferation of ever more repressive power over the American people, as well as the increasing limitations upon our personal freedoms, will not successfully be confronted simply by rage or anger. We must attempt to achieve a deeper understanding of what lies beneath these forces of domination.

Some years ago, Mitscherlich (1993) associated the concept of a "Society Without a Father" with the emergence of fascism and Hitler's rise to power in Germany. What might this mean for the present situation in the United States? First, looking at George W. Bush, one begins to question the nature of his relationship with his own father. There are, indeed, strong suggestions that his father was experienced as absent and that there was, then, no real competition with his father to lose. In the absense of such competition, an authentic sense of conscience is not established. This results, on the one hand, in a personal life characterized by an impaired sense of self-control (note Bush's admitted debauchery during his years at Yale, as well as his acknowledged history of substance abuse). This can lead to at least two situations.

First, even with the reliance upon his wife an external source of support for his personal life (as a "conscience" alias), this may well still leave him feeling vulnerable to a strong fear of internal fragmentation and loss of control. Thus, the need to project his fears onto the outside world, and the attempt to over-control the external environment, including his presidential control over us. In other words, George Bush as a mass leader acts as if he is superior to conscience, demanding a regressive obedience from us, as if we were unknowing children. Lacking a tie to the father, for Bush a genuine father-son conflict was absent at the time that the conscience was to be formed and ties to it were to be established.

In addition, with the unavailablity of a political sense of conscience, Bush has been forced again to seek and rely upon sources of external guidance in this area. Lacking even a primitive sense of self-cohesion, he has turned to those who will provide him with the mirroring transference needs of unqualified praise and admiration. Consequently, Bush has come to rely upon men such as Cheney, Rove and DeLay. More broadly, he has come to embrace the words of the born-again, evangelical Christian movement. However, lacking his own sense of internal conscience and judgement, Bush is left unable to evaluate either the motivations or guidance of those upon whom he relies.

Thus, on the one hand we are left with a president blindly following the dictates for ever-more expanding power, oppression of the less fortunate and the legitimization of abuse, even torture of those who question or oppose the proliferation of American political domination throughout the world. On the other hand, Bush's reliance upon the evangelical Christian movement as a source of conscience has led to the unprecedented intrusion of one particular religious sect or cult into the course of governmental and public life. More perilous, it has resulted in major governmental decisions being made in accordance with and to satisfy the dogmas of that particular religious movement.

Secondly, what makes our situation ever more dangerous is the convergence of a president thus impaired with the current state of American society. We are now a society that increasingly feels alienated from public life, forced into taking the role of passive victims of the immensely wealthy, technological advances at a rate almost beyond our grasp and unbelievable, corrupt politicians more interested in their own needs than those of their constituents. As a society, then, we have rapidly become a "fatherless" society, feeling a lack of internal control and self-determination.

Thus, largely unaware of our motivation, many of us desperately have sought a solution by making, as with George W. Bush, a distraught attempt to rigidly control our external world—and one aspect of this attempt has been to seek an ally to serve as The Father, The Law, and The Authority. We are making a dangerous liaison with Bush, who is desperately seeking the same thing.

These are dangerous times: History repeats itself.

THE N.Y. TIMES EDITORIAL:

"MR. CHENEY'S IMPERIAL PRESIDENCY"

George W. Bush has quipped several times during his political career that it would be so much easier to govern in a dictatorship. Apparently he never told his vice president that this was a joke.

Virtually from the time he chose himself to be Mr. Bush's running mate in 2000, Dick Cheney has spearheaded an extraordinary expansion of the powers of the presidency - from writing energy policy behind closed doors with oil executives to abrogating longstanding treaties and using the 9/11 attacks as a pretext to invade Iraq, scrap the Geneva Conventions and spy on American citizens.

It was a chance Mr. Cheney seems to have been dreaming about for decades. Most Americans looked at wrenching events like the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal and the Iran-contra debacle and worried that the presidency had become too powerful, secretive and dismissive. Mr. Cheney looked at the same events and fretted that the presidency was not powerful enough, and too vulnerable to inspection and calls for accountability.

The president "needs to have his constitutional powers unimpaired, if you will, in terms of the conduct of national security policy," Mr. Cheney said this week as he tried to stifle the outcry over a domestic spying program that Mr. Bush authorized after the 9/11 attacks.

Before 9/11, Mr. Cheney was trying to undermine the institutional and legal structure of multilateral foreign policy: he championed the abrogation of the Antiballistic Missile Treaty with Moscow in order to build an antimissile shield that doesn't work but makes military contractors rich. Early in his tenure, Mr. Cheney, who quit as chief executive of Halliburton to run with Mr. Bush in 2000, gathered his energy industry cronies at secret meetings in Washington to rewrite energy policy to their specifications. Mr. Cheney offered the usual excuses about the need to get candid advice on important matters, and the courts, sadly, bought it. But the task force was not an exercise in diverse views. Mr. Cheney gathered people who agreed with him, and allowed them to write national policy for an industry in which he had recently amassed a fortune.

The effort to expand presidential power accelerated after 9/11, taking advantage of a national consensus that the president should have additional powers to use judiciously against terrorists.

Mr. Cheney started agitating for an attack on Iraq immediately, pushing the intelligence community to come up with evidence about a link between Iraq and Al Qaeda that never existed. His team was central to writing the legal briefs justifying the abuse and torture of prisoners, the idea that the president can designate people to be "unlawful enemy combatants" and detain them indefinitely, and a secret program allowing the National Security Agency to eavesdrop on American citizens without warrants. And when Senator John McCain introduced a measure to reinstate the rule of law at American military prisons, Mr. Cheney not only led the effort to stop the amendment, but also tried to revise it to actually legalize torture at C.I.A. prisons.

There are finally signs that the democratic system is trying to rein in the imperial presidency. Republicans in the Senate and House forced Mr. Bush to back the McCain amendment, and Mr. Cheney's plan to legalize torture by intelligence agents was rebuffed. Congress also agreed to extend the Patriot Act for five weeks rather than doing the administration's bidding and rushing to make it permanent.

On Wednesday, a federal appeals court refused to allow the administration to transfer Jose Padilla, an American citizen who has been held by the military for more than three years on suspicion of plotting terrorist attacks, from military to civilian custody. After winning the same court's approval in September to hold Mr. Padilla as an unlawful combatant, the administration abruptly reversed course in November and charged him with civil crimes unrelated to his arrest. That decision was an obvious attempt to avoid having the Supreme Court review the legality of the detention powers that Mr. Bush gave himself, and the appeals judges refused to go along.

Mr. Bush and Mr. Cheney have insisted that the secret eavesdropping program is legal, but The Washington Post reported yesterday that the court created to supervise this sort of activity is not so sure. It said that the presiding judge was arranging a classified briefing for her fellow judges and that several judges on the court wanted to know why the administration believed eavesdropping on American citizens without warrants was legal when the law specifically required such warrants.

Mr. Bush and Mr. Cheney are tenacious. They still control both houses of Congress and are determined to pack the judiciary with like-minded ideologues. Still, the recent developments are encouraging, especially since the court ruling on Mr. Padilla was written by a staunch conservative considered by President Bush for the Supreme Court.

The New York Times

December 23, 2005

December 24, 2005

THIS BLOG IS ABOUT PSYCHOANALYSIS

Yes, this blog is about psychoanalysis. Each post, indeed the very sequence of posts, has been a discussion about psychoanalysis. Some readers might say that the commentaries really don't seem to be about psychoanalysis. Actually, this is because the practice of contemporary psychonalysis is completely different today, and quite unlike the public perception and presentation of psychoanalysis.

Thinking about psychoanalysis, one might begin with a discussion of the attacks upon Freud, which really are assaults upon the concept of being human. The attacks upon Freud, however, are made by those who are afraid of him. Those who are not afraid of him are free to think about what parts of his theories still apply today, and which do not. Further, when not influenced by the power of the fear of Freud, it becomes possible to think about how the transformation of some of his ideas (i.e., within the context of todays world) might make them quite useful in psychoanalysis, as well as in everyday life.

The following discussion about the attacks upon Freud is drawn from an article that I published,entitled "The Human Toll of Scientism":

Scientistic thinking would have us believe that we can achieve truth about our conscious selves and experiences, where in reality there are some human things which are indeed factual, but many other important human things which are more ambiguous and indeterminate.

The emergence of today's profusion of rapid-repair home remedies geared to temporary narcissistic rejuvenation may be seen as a response to the refusal to recognize the mysterious and sometimes tragic dimensions of life, which are in turn anchored in the ambiguities of both unconscious and conscious dimensions of human experience.

It is this broader rejection of ambiguity and uncertainly in our everyday lives which fosters the illusory hopes offered by the present-day explosion of self-help books about diet programs, exercise plans, techniques for finding the right romantic partner, practical schemes promising the quick accumulation of financial wealth, and various homespun remedies for the alleviation of specific neurotic symptoms.

Each of these practical strategic programs promises shortcuts to a particular version of human happiness, claiming to have exclusive knowledge about what the elusive nature of that happiness really is. The tunnel-visioned conviction that there are such shortcuts to human perfection signals a culture which is all too eager to ignore the deep, complex, and often darker dimensions of human existence.

But the driven cultural repudiation of Freud, and by implication of psychoanalysis and most forms of verbal psychotherapy, is not just a repudiation of the deep and unconscious dimensions of human experience, but it really involves the more broad-ranging attempt to avoid the more troubling questions about both unconscious and conscious human motivation and what makes life meaningful for an individual.

There are, of course, specific political implications of the scientistically-based cultural view that ignores the ambiguity of much of human motivation. The short-sighted approach to meaning as valid only to the extent that it is revealed by the straightforward application of reason results in a particular opinion about what citizens are like in our democratic society.

This view depicts humans largely as preference-expressing political atoms measured by political polls, or as consumer units reflected by the fluctuations of daily stock-exchange reports. In both cases, society becomes an aggregate of these atoms, and the only irrationality recognized in their existence is the failure of these preference-expressing units to conform to the rules of behavioral, learning, or rational-choice theories.

In contradistinction, the claim of psychoanalysis is that the world is not entirely rational, and the techniques of psychoanalysis are partly an attempt to take the ambiguities of both unconscious and conscious motivations into account in ways that makes them less likely to disrupt human life in confusing and sometimes destructive ways.

The attack upon Freud then becomes less an assault upon the father of psychoanalysis as upon the idea of indeterminacy in life, an attack upon the belief that that we are free agents in determining the courses of our lives, but also that as free agents there is no final resolution of indeterminacy through ever-more careful attention to ourselves in the efforts to determine our "true" aims and to decide which compromises in life are ultimately "best."

With the acceptance of this kind of indeterminacy, there is an awareness that ambiguity is not temporary, but rather that ultimately ambiguity is irreducible. Human choice always involves choosing one course of action, while abandoning others, some of which may be in some respects equally preferable.

The attempt to restrict the foundation of human choices to empirical rules obscures the ambiguity inherent in many of our important decisions by creating the myth that there are some good ways and some bad ways, and that ultimately we can always come to "know" the differences between those paths.

But in many important decisions to do something, there is no linear, temporal relationship between thought and action. In those cases, our choices emerge largely as an expression of an indefinite number of both formulated and unformulated influences within the individual's experiences.

The scientistic assault represents an evasion of the belief that humans are in the painful condition of having the potential to make more meanings than we can knowingly grasp, an evasion through the flight into the illusion of scientific certainty and the wish that human choices could ultimately be technologically rational.

But in fact, since there are many things which cannot be found out by the methods of natural science and practical reason, the conviction spreads within our culture that we do not need to find out about these things. And then, since we do not need to find out about certain things, in a sense we come to live in the fantasy that somehow we already know about all of the things that really matter. This illusory equation of science with certainty as leading to a culture of "knowingness."

With the glorification of the rational mind, pure reason becomes associated with the belief that only it can solve any problem, an association which is made possible by the fact that it cannot or refuses to acknowledge the kinds of existential problems it cannot methodically solve. The claim to "already know" distorts any real attempts to discover or find out about dimensions of meaning and life which do not conform to the belief that practical reason can solve every problem.

This is the true essence of the attacks upon Freud and psychoanalysis, the advancement of a dangerous belief that if psychoanalytic ways of thinking can be empirically discounted, there will no longer be any need to either recognize or account for the fact that ultimately the world of human motivation and meaning is ambiguous.

In other words, killing Freud ultimately stands for a reaffirmation of the scientistic self-assurance that all real human problems can be both formulated and resolved solely through the readily apparent, methodical application of practical, scientistic reason.

Unfortunately, it also stands to some degree as a renunciation of the uniquely human freedom we each exercise in ultimately being responsible for choosing our own particular courses of action in life.

Thinking about psychoanalysis, one might begin with a discussion of the attacks upon Freud, which really are assaults upon the concept of being human. The attacks upon Freud, however, are made by those who are afraid of him. Those who are not afraid of him are free to think about what parts of his theories still apply today, and which do not. Further, when not influenced by the power of the fear of Freud, it becomes possible to think about how the transformation of some of his ideas (i.e., within the context of todays world) might make them quite useful in psychoanalysis, as well as in everyday life.

The following discussion about the attacks upon Freud is drawn from an article that I published,entitled "The Human Toll of Scientism":

Scientistic thinking would have us believe that we can achieve truth about our conscious selves and experiences, where in reality there are some human things which are indeed factual, but many other important human things which are more ambiguous and indeterminate.

The emergence of today's profusion of rapid-repair home remedies geared to temporary narcissistic rejuvenation may be seen as a response to the refusal to recognize the mysterious and sometimes tragic dimensions of life, which are in turn anchored in the ambiguities of both unconscious and conscious dimensions of human experience.

It is this broader rejection of ambiguity and uncertainly in our everyday lives which fosters the illusory hopes offered by the present-day explosion of self-help books about diet programs, exercise plans, techniques for finding the right romantic partner, practical schemes promising the quick accumulation of financial wealth, and various homespun remedies for the alleviation of specific neurotic symptoms.

Each of these practical strategic programs promises shortcuts to a particular version of human happiness, claiming to have exclusive knowledge about what the elusive nature of that happiness really is. The tunnel-visioned conviction that there are such shortcuts to human perfection signals a culture which is all too eager to ignore the deep, complex, and often darker dimensions of human existence.

But the driven cultural repudiation of Freud, and by implication of psychoanalysis and most forms of verbal psychotherapy, is not just a repudiation of the deep and unconscious dimensions of human experience, but it really involves the more broad-ranging attempt to avoid the more troubling questions about both unconscious and conscious human motivation and what makes life meaningful for an individual.

There are, of course, specific political implications of the scientistically-based cultural view that ignores the ambiguity of much of human motivation. The short-sighted approach to meaning as valid only to the extent that it is revealed by the straightforward application of reason results in a particular opinion about what citizens are like in our democratic society.

This view depicts humans largely as preference-expressing political atoms measured by political polls, or as consumer units reflected by the fluctuations of daily stock-exchange reports. In both cases, society becomes an aggregate of these atoms, and the only irrationality recognized in their existence is the failure of these preference-expressing units to conform to the rules of behavioral, learning, or rational-choice theories.

In contradistinction, the claim of psychoanalysis is that the world is not entirely rational, and the techniques of psychoanalysis are partly an attempt to take the ambiguities of both unconscious and conscious motivations into account in ways that makes them less likely to disrupt human life in confusing and sometimes destructive ways.

The attack upon Freud then becomes less an assault upon the father of psychoanalysis as upon the idea of indeterminacy in life, an attack upon the belief that that we are free agents in determining the courses of our lives, but also that as free agents there is no final resolution of indeterminacy through ever-more careful attention to ourselves in the efforts to determine our "true" aims and to decide which compromises in life are ultimately "best."

With the acceptance of this kind of indeterminacy, there is an awareness that ambiguity is not temporary, but rather that ultimately ambiguity is irreducible. Human choice always involves choosing one course of action, while abandoning others, some of which may be in some respects equally preferable.

The attempt to restrict the foundation of human choices to empirical rules obscures the ambiguity inherent in many of our important decisions by creating the myth that there are some good ways and some bad ways, and that ultimately we can always come to "know" the differences between those paths.

But in many important decisions to do something, there is no linear, temporal relationship between thought and action. In those cases, our choices emerge largely as an expression of an indefinite number of both formulated and unformulated influences within the individual's experiences.

The scientistic assault represents an evasion of the belief that humans are in the painful condition of having the potential to make more meanings than we can knowingly grasp, an evasion through the flight into the illusion of scientific certainty and the wish that human choices could ultimately be technologically rational.

But in fact, since there are many things which cannot be found out by the methods of natural science and practical reason, the conviction spreads within our culture that we do not need to find out about these things. And then, since we do not need to find out about certain things, in a sense we come to live in the fantasy that somehow we already know about all of the things that really matter. This illusory equation of science with certainty as leading to a culture of "knowingness."

With the glorification of the rational mind, pure reason becomes associated with the belief that only it can solve any problem, an association which is made possible by the fact that it cannot or refuses to acknowledge the kinds of existential problems it cannot methodically solve. The claim to "already know" distorts any real attempts to discover or find out about dimensions of meaning and life which do not conform to the belief that practical reason can solve every problem.

This is the true essence of the attacks upon Freud and psychoanalysis, the advancement of a dangerous belief that if psychoanalytic ways of thinking can be empirically discounted, there will no longer be any need to either recognize or account for the fact that ultimately the world of human motivation and meaning is ambiguous.

In other words, killing Freud ultimately stands for a reaffirmation of the scientistic self-assurance that all real human problems can be both formulated and resolved solely through the readily apparent, methodical application of practical, scientistic reason.

Unfortunately, it also stands to some degree as a renunciation of the uniquely human freedom we each exercise in ultimately being responsible for choosing our own particular courses of action in life.

December 23, 2005

Goodnight Moon Again...

It has been a long pre-Christmas week, a bit of tending to others. This may well be a night to fall asleep quite early.

Many startling experiences are included in the notion of falling. We fall silent. We fall in love. We fall for the other. When something is beautiful or compelling, we think of it as being beyond falling--it is "drop dead" or "to die for." These expressions, for lack of a better phrase, all convey visions of the ways in which we give ourselves over to the

other.

And so, I shall fall asleep. It will be a cozy time, as you can see from the very private glimpse of my simple bedroom pictured here.

Goodnight moon...

Many startling experiences are included in the notion of falling. We fall silent. We fall in love. We fall for the other. When something is beautiful or compelling, we think of it as being beyond falling--it is "drop dead" or "to die for." These expressions, for lack of a better phrase, all convey visions of the ways in which we give ourselves over to the

other.

And so, I shall fall asleep. It will be a cozy time, as you can see from the very private glimpse of my simple bedroom pictured here.

Goodnight moon...

Holiday Greetings: A Picasso Peace Dove

December 22, 2005

Christmas: Just Keep Lookin' Up at that Yonder Star...

LAST MINUTE CHRISTMAS GIFTS:

Three of only six original and numbered, hand-crafted Krinner Bavarian Christmas tree stands are still available from the Chalet in Wilmette (IL). Only $499 each: for those who have everything and want more.

Gift certificates may be purchased from BELLHOP, a company that will come to your comfortable and very exclusive home, pick up all of your luggage and have it waiting at your destination hotel when you arrive. For those who have everything and want someone else to carry it as well.

The KeepVerySafe Bedside Table, which can be quickly transformed into a shield and truncheon, is obtainable (a limited edition of 100) for $2,115 each from James McAdam, Inc. For those who have everthing and nobody better try to get any of it.

Hope you find these last-minute shoppin' hints useful. Happy Holidays!

Three of only six original and numbered, hand-crafted Krinner Bavarian Christmas tree stands are still available from the Chalet in Wilmette (IL). Only $499 each: for those who have everything and want more.

Gift certificates may be purchased from BELLHOP, a company that will come to your comfortable and very exclusive home, pick up all of your luggage and have it waiting at your destination hotel when you arrive. For those who have everything and want someone else to carry it as well.

The KeepVerySafe Bedside Table, which can be quickly transformed into a shield and truncheon, is obtainable (a limited edition of 100) for $2,115 each from James McAdam, Inc. For those who have everthing and nobody better try to get any of it.

Hope you find these last-minute shoppin' hints useful. Happy Holidays!

December 21, 2005

President Bush Assumed Dictatorial Power to Order Top-Secret Domestic Spying

Bush and Cheney are saying that the briefings that Hill leaders got on his domestic spying operation demonstrate how respectful they are of oversight, checks and balances, advise & consent -- you know, the kind of freedom stuff we're fighting for in Iraq.

But take a look at this letter, just released by Senator Jay Rockefeller, the ranking Democrat on the Intelligence Committee.

He wrote it to Cheney in 2003, after he learned about the wiretapping without FISA court approval maneuver. It's handwritten -- because no one in the meeting could tell anyone else about it, not even a typist.

Rockefeller told Cheney he could not endorse the program. He said he was keeping a sealed copy of the letter -- for a moment just like this.

Doubtless Republican Pat Roberts, the Kansas toady who chairs the Senate Intelligence Committee, got with the Bush program; after all, he's the one who's stopped the investigation of Administration misuse of pre-war intelligence for nearly two years, until Harry Reid forced the Senate into private session.

Bush says we should trust him, because he swore an oath of office. If his briefings of Congress on domestic spying are an example of what he thinks it means to submit to oversight, maybe this will stiffen the spine of some Democrats enough for them now to tell the White House what advise and consent really means -- and the matter of Sam Alito provides an awfully appropriate opportunity to do that.

Marty Kaplan

HuffingtonPost

12/20/2005

But take a look at this letter, just released by Senator Jay Rockefeller, the ranking Democrat on the Intelligence Committee.

He wrote it to Cheney in 2003, after he learned about the wiretapping without FISA court approval maneuver. It's handwritten -- because no one in the meeting could tell anyone else about it, not even a typist.

Rockefeller told Cheney he could not endorse the program. He said he was keeping a sealed copy of the letter -- for a moment just like this.

Doubtless Republican Pat Roberts, the Kansas toady who chairs the Senate Intelligence Committee, got with the Bush program; after all, he's the one who's stopped the investigation of Administration misuse of pre-war intelligence for nearly two years, until Harry Reid forced the Senate into private session.

Bush says we should trust him, because he swore an oath of office. If his briefings of Congress on domestic spying are an example of what he thinks it means to submit to oversight, maybe this will stiffen the spine of some Democrats enough for them now to tell the White House what advise and consent really means -- and the matter of Sam Alito provides an awfully appropriate opportunity to do that.

Marty Kaplan

HuffingtonPost

12/20/2005

Full Frontal Assault: Academics Continue Attack of Bloggers

Bloggers Need Not Apply

"Job seekers need to eliminate as many negatives as possible, and in most cases a blog turns out to be a negative"

By IVAN TRIBBLE

What is it with job seekers who also write blogs? Our recent faculty search at Quaint Old College resulted in a number of bloggers among our semifinalists. Those candidates looked good enough on paper to merit a phone interview, after which they were still being seriously considered for an on-campus interview.

That's when the committee took a look at their online activity.

In some cases, a Google search of the candidate's name turned up his or her blog. Other candidates told us about their Web site, even making sure we had the URL so we wouldn't fail to find it. One candidate mentioned it in the cover letter. We felt compelled to follow up in those instances, and it turned out to be every bit as eye-opening as a train wreck.

Don't get me wrong: Our initial thoughts about blogs were, if anything, positive. It was easy to imagine creative academics carrying their scholarly activity outside the classroom and the narrow audience of print publications into a new venue, one more widely available to the public and a tech-savvy student audience.

We wanted to hire somebody in our stack of finalists, so we gave the same benefit of the doubt to the bloggers as to the others in the pool.

A candidate's blog is more accessible to the search committee than most forms of scholarly output. It can be hard to lay your hands on an obscure journal or book chapter, but the applicant's blog comes up on any computer. Several members of our search committee found the sheer volume of blog entries daunting enough to quit after reading a few. Others persisted into what turned out, in some cases, to be the dank, dark depths of the blogger's tormented soul; in other cases, the far limits of techno-geekdom; and in one case, a cat better off left in the bag.

The pertinent question for bloggers is simply, Why? What is the purpose of broadcasting one's unfiltered thoughts to the whole wired world? It's not hard to imagine legitimate, constructive applications for such a forum. But it's also not hard to find examples of the worst kinds of uses.

A blog easily becomes a therapeutic outlet, a place to vent petty gripes and frustrations stemming from congested traffic, rude sales clerks, or unpleasant national news. It becomes an open diary or confessional booth, where inward thoughts are publicly aired.

Worst of all, for professional academics, it's a publishing medium with no vetting process, no review board, and no editor. The author is the sole judge of what constitutes publishable material, and the medium allows for instantaneous distribution. After wrapping up a juicy rant at 3 a.m., it only takes a few clicks to put it into global circulation.

We've all done it -- expressed that way-out-there opinion in a lecture we're giving, in cocktail-party conversation, or in an e-mail message to a friend. There is a slight risk that the opinion might find its way to the wrong person's attention and embarrass us. Words said and e-mail messages sent cannot be retracted, but usually have a limited range. When placed on prominent display in a blog, however, all bets are off.

So, to the job seekers.

Professor Turbo Geek's blog had a presumptuous title that was easy to overlook, as we see plenty of cyberbravado these days in the online aliases and e-mail addresses of students and colleagues. But the site quickly revealed that the true passion of said blogger's life was not academe at all, but the minutiae of software systems, server hardware, and other tech exotica. It's one thing to be proficient in Microsoft Office applications or HTML, but we can't afford to have our new hire ditching us to hang out in computer science.

Professor Shrill ran a strictly personal blog, which, to the author's credit, scrupulously avoided comment about the writer's current job, coworkers, or place of employment. But it's best for job seekers to leave their personal lives mostly out of the interview process.

It would never occur to the committee to ask what a candidate thinks about certain people's choice of fashion or body adornment, which countries we should invade, what should be done to drivers who refuse to get out of the passing lane, what constitutes a real man, or how the recovery process from one's childhood traumas is going. But since the applicant elaborated on many topics like those, we were all ears. And we were a little concerned. It's not our place to make the recommendation, but we agreed that a little therapy (of the offline variety) might be in order.

Finally we come to Professor Bagged Cat. He was among the finalists we brought to campus for an interview, which he royally bombed, so we were leaning against him anyway. But we were irritated to find out, late in the process, that he had misrepresented his research, ostensibly to make it seem more relevant to a hot issue in the news lately. For privacy reasons, I'm not going to go into the details, but we were dismayed to find a blog that made clear that the candidate's research was not as independent or relevant as he had made it seem. We felt deceived by his overstatement of his academic expertise.

Job seekers who are also bloggers may have a tough road ahead, if our committee's experience is any indication. You may think your blog is harmless and use the faulty logic of the blogger, "Oh, no one will see it anyway." Don't count on it.

The content of the blog may be less worrisome than the fact of the blog itself. Several committee members expressed concern that a blogger who joined our staff might air departmental dirty laundry (real or imagined) on the cyber clothesline for the world to see. Past good behavior is no guarantee against future lapses of professional decorum.

A colleague from a different university provides this cautionary tale: After graduation, a student goes to the far side of the world to teach English. Student sends delightful travelogue home via e-mail messages, and recipients encourage student to record rare experiences in a blog. A year passes and the blog turns into a detailed personal gripe session about the job. It is discovered and devoured by students, coworkers, and place of employment. Shamed student turns for support to alma-mater faculty members, who read the blog and chastise student for lack of professionalism and for tainting alma mater's reputation. Student now seeks other job -- without letters of recommendation from current employer or alma mater.

Not every case is so consequential. And in truth we did not disqualify any applicants based purely on their blogs. If the blog was a negative factor, it was one of many that killed a candidate's chances.

More often that not, however, the blog was a negative, and job seekers need to eliminate as many negatives as possible.

We've seen the hapless job seekers who destroy the good thing they've got going on paper by being so irritating in person that we can't wait to put them back on a plane. Our blogger applicants came off reasonably well at the initial interviews, but once we hung up the phone and called up their blogs, we got to know "the real them" -- better than we wanted, enough to conclude we didn't want to know more.

Ivan Tribble is the pseudonym of a humanities professor at a small liberal-arts college in the Midwest.

The Chronicle of Higher Education

December 19, 2005

December 17, 2005

New Beginnings: On Facing the Unknown

Thinking indoors, inside. Complexly simple, liminal considerations about making it possible for us to listen and hear or feel ourselves in a new way:

With the growing plurality of theoretical schools in the arts, social sciences and psychoanalysis (and many other fields), as well as the post-positivist turn in our thinking about theory itself and its relation to truth, there is a new urgency about our relation to the observational data of everyday life. On the one hand, we can no longer presume any definitively correct theoretical framework. Even if we are ourselves persuaded about the truth of our own particular perspective, we are forced to be modest about its claim on reality. This is the lesson of pluralism.

Conversely, we are increasingly forced to recognize that the facts, the data themselves, are always imbued with meaning. That is, there is no clear distinction to be made between facts and theories; there is no place to stand apart from our theories. If truth with a capital "T" is no longer attainable, even the particular local truths of a given situation are contingent and provisional, laced with ambiguity and uncertainty. Our interpretations rest on interpretations, rest on interpretations, rest on interpretations. This is the lesson of post-positivist science.

The emphasis upon the ambiguous and uncertain nature of our lives vitalizes and enriches our experiences of surprise. In other words, expanding our capacities to become engaged in depth with the ongoing events in our lives requires that we learn to become prepared to be unprepared for new experiences. This is an important characteristic of being open, or of openness. It is complemented by being prepared to make mistakes, no matter how diligently we attempt to receive the unknown. Here the stress is on having the flexibility to recover and re-find one's bearings.

This being said, it is nevertheless very difficult fully to accept that we are, whether artists, scientists (or whatever mix) always taking temporary, limited and highly personal sightings in endlessly changing circumstances, sightings marked not only by new corrections but also by new errors. We can never know how to do that, but we can know that that is what we have to do.

Once one's mind has been freed of its repetitive ruminations over what it is afraid to face, or its compulsive need to hang on to what it believes it knows, it becomes able to truly question the unknown that is actually there. There is a parallel shift from attempting to create meaning from reconstructions of the past to the realm of the "living moment" in which one is an inquiring subject. From this perspective, we are always asking questions. Our questions are always in search of other questions, and of the questions of others.

There are reasons why the unknown often is kept at bay in the present, reasons derived from old experience. If the notion of the dynamic unconscious is less viable as the crucial point of origin for repressed impulses, it is nonetheless true that there are dynamic processes that actively work to screen our perceptions and curtail our activities in order to protect us from encountering what past experience have made us afraid to know.

Further, the realm of the unknown is in itself is a source of fear. We may be able to contemplate the vastness of space with awe, for example, but when we actually venture into it we become acutely aware of needing to know more than we do. Our relation to unknown places demands upon us to know what we cannot know. It is not surprising that being able to tolerate this confrontation with the unknown often requires us temporarily to "stand back," something analogous to creating a space in which to move. Such a space allows us to recover or develop the capacity to think about what has previously not been available for thought. For this to happen, an "opening" has to occur in the mind within which the new potential for thinking can occur.

"Space" is used a metaphor here, but as one of those metaphors which allows perspective to develop and reflection arise. If we can "stand back" from an initially overwhelming immediate experience, we are creating something that can be thought of as a "distance" that allows a new relationship between experience and thought. Or one might think of it in terms of time: a delay or a pause that occurs between the act and the thought, which makes it possible for us to listen and hear or feel ourselves in a new way.

Note: I'm pleased to let readers know that the first version of the Preface to The Restoration of Hope has been composed. It is available for you to read through the link for the book/monograph, which is located to the left in the sidebar.

With the growing plurality of theoretical schools in the arts, social sciences and psychoanalysis (and many other fields), as well as the post-positivist turn in our thinking about theory itself and its relation to truth, there is a new urgency about our relation to the observational data of everyday life. On the one hand, we can no longer presume any definitively correct theoretical framework. Even if we are ourselves persuaded about the truth of our own particular perspective, we are forced to be modest about its claim on reality. This is the lesson of pluralism.

Conversely, we are increasingly forced to recognize that the facts, the data themselves, are always imbued with meaning. That is, there is no clear distinction to be made between facts and theories; there is no place to stand apart from our theories. If truth with a capital "T" is no longer attainable, even the particular local truths of a given situation are contingent and provisional, laced with ambiguity and uncertainty. Our interpretations rest on interpretations, rest on interpretations, rest on interpretations. This is the lesson of post-positivist science.

The emphasis upon the ambiguous and uncertain nature of our lives vitalizes and enriches our experiences of surprise. In other words, expanding our capacities to become engaged in depth with the ongoing events in our lives requires that we learn to become prepared to be unprepared for new experiences. This is an important characteristic of being open, or of openness. It is complemented by being prepared to make mistakes, no matter how diligently we attempt to receive the unknown. Here the stress is on having the flexibility to recover and re-find one's bearings.

This being said, it is nevertheless very difficult fully to accept that we are, whether artists, scientists (or whatever mix) always taking temporary, limited and highly personal sightings in endlessly changing circumstances, sightings marked not only by new corrections but also by new errors. We can never know how to do that, but we can know that that is what we have to do.

Once one's mind has been freed of its repetitive ruminations over what it is afraid to face, or its compulsive need to hang on to what it believes it knows, it becomes able to truly question the unknown that is actually there. There is a parallel shift from attempting to create meaning from reconstructions of the past to the realm of the "living moment" in which one is an inquiring subject. From this perspective, we are always asking questions. Our questions are always in search of other questions, and of the questions of others.

There are reasons why the unknown often is kept at bay in the present, reasons derived from old experience. If the notion of the dynamic unconscious is less viable as the crucial point of origin for repressed impulses, it is nonetheless true that there are dynamic processes that actively work to screen our perceptions and curtail our activities in order to protect us from encountering what past experience have made us afraid to know.

Further, the realm of the unknown is in itself is a source of fear. We may be able to contemplate the vastness of space with awe, for example, but when we actually venture into it we become acutely aware of needing to know more than we do. Our relation to unknown places demands upon us to know what we cannot know. It is not surprising that being able to tolerate this confrontation with the unknown often requires us temporarily to "stand back," something analogous to creating a space in which to move. Such a space allows us to recover or develop the capacity to think about what has previously not been available for thought. For this to happen, an "opening" has to occur in the mind within which the new potential for thinking can occur.

"Space" is used a metaphor here, but as one of those metaphors which allows perspective to develop and reflection arise. If we can "stand back" from an initially overwhelming immediate experience, we are creating something that can be thought of as a "distance" that allows a new relationship between experience and thought. Or one might think of it in terms of time: a delay or a pause that occurs between the act and the thought, which makes it possible for us to listen and hear or feel ourselves in a new way.

Note: I'm pleased to let readers know that the first version of the Preface to The Restoration of Hope has been composed. It is available for you to read through the link for the book/monograph, which is located to the left in the sidebar.

Reflections: The Transformation of Hope

An initial version or model of the monograph, "The Transformation of Hope", is now posted online. At this early stage, only the Table of Contents is available, but the Preface will be published tomorrow. Readers are very cordially invited to preview that page by visiting the link to "Transformation of Hope: A Book", which is provided in the sidebar on the left.

I genuinely hope that readers might find tomorrow's opening discussion in that monograph to be challenging, engaging and creatively stimulating. The process of thinking about these writings has contributed to my own sense of the poignancy of the human longing for change and growth against the background of inescapable loss.

I am very deeply indebteded to the patience, guidance and wisdom of the late Merton M. Gill, M.D., Aaron A. Hilkevitch, M.D. and Irwin Z. Hoffman, Ph.D.

I genuinely hope that readers might find tomorrow's opening discussion in that monograph to be challenging, engaging and creatively stimulating. The process of thinking about these writings has contributed to my own sense of the poignancy of the human longing for change and growth against the background of inescapable loss.

I am very deeply indebteded to the patience, guidance and wisdom of the late Merton M. Gill, M.D., Aaron A. Hilkevitch, M.D. and Irwin Z. Hoffman, Ph.D.

December 12, 2005

Alone: A Little Night Coffee

I've been reflecting upon the project that was begun here recently, i.e., to review the postings from the earliest to the most recent, in terms of their underlying reference to contemporary relational theory. The structure of that undertaking was, however, flawed. Specifically, to have the most recent discussions focus sequentially upon the earliest commentaries is inherently confusing.

The most coherent manner in which this plan can be carried out, it seems, is to produce it as a separate monograph online, which can be accessed by a prominent link from this page. The Preface for this monograph will be available shortly.

In the meantime, a "thought-teaser":

Did you know that Lewis Carroll ("Alice in Wonderland") was also a Lecturer in Mathematics at Oxford University, as well as being a lay magician? Here is a puzzle that he created, which is also a metaphor for the very confusion that I faced (created?) when using a series proceeding from the present to describe a series proceeding from a beginning.

He called it a "syzynergy" or "yoke." It consists of beginning with one word, taking out a consecutive set of letters from that word & adding new letters to form a new word, doing the process again (and again) until one ends up with the (seeming) opposite of the first word.

CONSERVATIVE (to)

LIBERAL

Conservative

servati

reservations

ation

deliberation

libera

Liberal

I'll be back in a bit.

December 11, 2005

MORTALITY AND REMINISCENCE

We Shall Pause...

Later today, I'll be introducing some thoughts that were evoked while directing my attention to some of the last few commentaries, a brief reminiscence that fostered a different perspective with regard to those earlier condensed reflections.

December 05, 2005

THE DAWN

II. ANTICIPATION.

Returning to my earlier discussions, after yesterday's pause in order to provide an update on blogger Daniel Denzler's good fortune, the second brief commentary (1/11/2005) was entitled The Dawn.

The refections on these concise remarks will examine topics that include beginnings, feelings of anticipation,and unknown experiences or challenges. There will also be references to the acceptance of uncertainty as it relates to the formal recognition of mortality.

New beginnings that offer the possibility of genuine meaning have a foundation based upon a confrontation with the reality of our own deaths, as well as those of our loved ones. It concerns mortality, or the awareness of mortality in our lives. A steadfast acceptance of one's mortality calls for an unflinching awareness of the inevitability of death, of the devastating losses that will probably precede it, and of the ceaseless threat of meaninglessness and despair brought on by this awareness. Creation of a meaningful life from within such existential awareness is courageous. In the face of the crushing reality of death, what remains is a need to turn away from it enough to affirm life.

The dialectic of our sense of being and our sense of our mortality is superordinate to all the others. It is the paradoxical foundation for our sense of meaning. Our finitude, our mortality, is our greatest limitation and yet the one that gives all others their significance. If we were eternal, meanings would not last forever-they would disappear.

It is only our awareness of the fragility and the inevitable death of what means most to us that gives our meanings life. Meaning, in other words, begins in dialectic, and dialectic remains the only soil in which it can grow. An undaunted acceptance of our mortality in both our thinking everyday lives is the philosophical heart the relational perspective that is being introduced in this series of discussions.

Returning to my earlier discussions, after yesterday's pause in order to provide an update on blogger Daniel Denzler's good fortune, the second brief commentary (1/11/2005) was entitled The Dawn.

The refections on these concise remarks will examine topics that include beginnings, feelings of anticipation,and unknown experiences or challenges. There will also be references to the acceptance of uncertainty as it relates to the formal recognition of mortality.

New beginnings that offer the possibility of genuine meaning have a foundation based upon a confrontation with the reality of our own deaths, as well as those of our loved ones. It concerns mortality, or the awareness of mortality in our lives. A steadfast acceptance of one's mortality calls for an unflinching awareness of the inevitability of death, of the devastating losses that will probably precede it, and of the ceaseless threat of meaninglessness and despair brought on by this awareness. Creation of a meaningful life from within such existential awareness is courageous. In the face of the crushing reality of death, what remains is a need to turn away from it enough to affirm life.

The dialectic of our sense of being and our sense of our mortality is superordinate to all the others. It is the paradoxical foundation for our sense of meaning. Our finitude, our mortality, is our greatest limitation and yet the one that gives all others their significance. If we were eternal, meanings would not last forever-they would disappear.

It is only our awareness of the fragility and the inevitable death of what means most to us that gives our meanings life. Meaning, in other words, begins in dialectic, and dialectic remains the only soil in which it can grow. An undaunted acceptance of our mortality in both our thinking everyday lives is the philosophical heart the relational perspective that is being introduced in this series of discussions.

Archives

January 2005 February 2005 March 2005 April 2005 May 2005 June 2005 July 2005 August 2005 September 2005 October 2005 November 2005 December 2005 January 2006 February 2006 March 2006 April 2006 May 2006 June 2006 July 2006 August 2006 October 2006 November 2006 December 2006 January 2007

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]